Difference between revisions of "Gut-Brain Connection: Leaky Gut/Leaky Brain, Microbiome (gut bugs)"

(gut section through gut dysbiosis) |

(gut section through vagus nerve) |

||

| Line 251: | Line 251: | ||

[https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304394016300775?via%3Dihub '''Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health?'''](Megan W.Bourassa et al, Jun 2016) | [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304394016300775?via%3Dihub '''Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health?'''](Megan W.Bourassa et al, Jun 2016) | ||

[[File:Vagus_nerve2.jpg|thumbnail|The vagus nerve extends from the brain to the gut. Source: Vagus Nerve https://biologydictionary.net/vagus-nerve/ ]] | |||

[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5414803/ '''Minireview: Gut Microbiota: The Neglected Endocrine Organ'''](Gerard Clarke et al, 3 Jun 2014) | [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5414803/ '''Minireview: Gut Microbiota: The Neglected Endocrine Organ'''](Gerard Clarke et al, 3 Jun 2014) | ||

[https://mbio.asm.org/content/5/3/e00853-14 Impacts of Plant-Based Foods in Ancestral Hominin Diets on the Metabolism and Function of Gut Microbiota In Vitro](Gary S. Frost et al, May 2014) | [https://mbio.asm.org/content/5/3/e00853-14 '''Impacts of Plant-Based Foods in Ancestral Hominin Diets on the Metabolism and Function of Gut Microbiota In Vitro'''](Gary S. Frost et al, May 2014) | ||

[https://academic.oup.com/advances/article/4/6/587/4595564 '''Resistant Starch: Promise for Improving Human Health'''](Diane F. Birt et al Nov 2013) | [https://academic.oup.com/advances/article/4/6/587/4595564 '''Resistant Starch: Promise for Improving Human Health'''](Diane F. Birt et al Nov 2013) | ||

=== VAGUS NERVE === | |||

The Vagus Nerve is what physically connects the gut to the brain. The vagus nerve is one of the longest nerves in the body extending from the brain to the gut. Signals are sent through the nerve in both directions. | |||

For information on the Vagus Nerve, including how to tap into the Vagus Nerve for healing purposes, see [[Vagus Nerve]] | |||

Revision as of 19:58, 25 November 2020

Introduction

Health of the gut (intestines) plays an important role in the health of the brain. The gut contains 500 million neurons and holds trillions of microbes which in turn make other chemicals that affect how the brain works. But inflammatory lifestyle and dietary habits that effect the gut can give rise to a sequence of events which trigger neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases.

Communication between the gut and the brain is called the gut-brain axis. The connection is both physical and biochemical. The physical connection is through the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve is one of the longest nerves in the body extending from the brain to the gut and signals are sent through it in both directions.

Biochemical communication comes from neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that transmit signals from nerve cells to target cells.

The gut contains a microbiome. The microbiome refers to the microbes and their genetic material. Gut microbiota, sometimes called gut flora or “gut bugs” refers to the microorganisms themselves and include: bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, and archaea. The microbiome is not static, it varies by individual and is influenced by many factors such that its composition changes continuously. The microbiome can contain both beneficial microbes as well as undesirable pathogens. Ideally these gut bugs are in balance. But when the overall diversity is diminished and there’s an overgrowth of bad microbiota (bad bugs) the result is gut dysbiosis. The gut can be likened to a garden, when nurtured, it flourishes with healthful flora or if neglected it becomes overcome by noxious weeds.

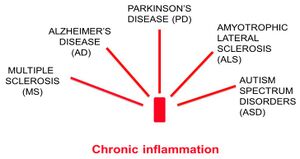

The digestive tract contains the largest component of the body’s immune system so the gut-brain axis is also connected through the body’s immune system. If your immune system is switched on for too long, it can lean to chronic inflammation, which is associated with a number of brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s Disease. [Source: The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease (Sian-Marie Lucas et al, 9 Jan 2006)]

In the "gut-brain axis" the gut and its microbial inhabitants send signals to the brain, and vice versa. For further reading: Gut communicates with the entire brain through cross-talking neurons

Some Introductory videos on this subject

- An introductory, illustrative video (not a person talking), only 5 minutes long, includes a transcript How the food you eat affects your gut

Gut concerns and strategies for improvement

Research shows that there is a difference in microbiota diversity and abundance between ApoE genotypes. The deficiencies ApoE4s hold could be a driver in our greater association with Alzheimer’s. [Source: APOE genotype influences the gut microbiome structure and function in humans and mice: relevance for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology(Tam T. T. Tran et al, 8 Apr 2019)] Gut dysbiosis can lead to leaky gut and leaky gut can lead to “leaky brain.” Leaky brain produces neuroinflammation in the brain which can cause Alzheimer’s Disease and certainly ApoE4s are more susceptible to inflammation. Inflammation disrupts the blood brain barrier, so potentially ApoE4s are more susceptible to “leaky brain.”

For further reading on differences the gut microbiome among APOE alleles, see Murine Gut Microbiome Association With APOE Alleles(Ishita J. Parikh et al, 14 Feb 2020).

LEAKY GUT

Although some medical professional refuse to admit that leaky gut is even a real condition, the published papers presenting evidence of its existence and the subsequent negative effects are numerous, have been growing impressively in recent years, and continue to grow.

Leaky gut, or increased permeability of the intestinal mucosa, is a very common ailment largely attributed to the Western Diet. Leaky gut is the most common cause of chronic inflammation, which in turn can compromise the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB) setting up neuroinflammation. But the inflammation, while chronic, can be low grade, therefore subtle and sometimes overlooked.

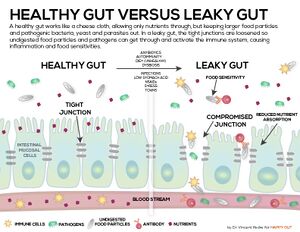

In a healthy gut, the epithelial cells (the cells that cover a surface) in the lining of intestinal walls are aligned very close to each other, called tight junctions. These tight junctions allow water and nutrients to pass through to the bloodstream but prohibit harmful substances of the intestines from passing through. In a leaky gut, these tight junctions are degraded allowing harmful food particles, bacteria, and toxins to enter directly into the bloodstream. The immune system responds to these leaked materials resulting in inflammation. This is how the process is supposed to work, the immune system tamps down inflammation to return to homeostasis (relatively stable equilibrium), issues develop when the immune system has to respond to continuous (chronic) inflammation and becomes overworked. Leaky gut is the most common cause of chronic inflammation and inflammation is associated with a number of brain disorders including Alzheimer’s Disease.

Of particular interest when it comes to leaky gut are lipopolysaccharides (LPS). LPS are a significant cause of inflammation and the researchers of this paper, Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Lipopolysaccharide as Mediators Between Gut Dysbiosis and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease found that high blood levels of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) were associated with large amyloid deposits in the brain, a condition associated with Alzheimer’s Disease.

A leaky gut is one of the three ways LPS enter the bloodstream with toxic results. Lipopolysaccharides are bacterial toxins in the body (an endotoxin) but they are usually contained safely within the gut. But if (1) the gut becomes leaky, or (2) if there is an infection or (3) a person’s diet contains too many fatty foods, lipopolysaccharides enter the bloodstream and become toxic.

LPS are found on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. The largest concentration of Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli and Salmonella, are found in the gut. If LPS remain in the gut, they don’t activate the immune system or cause harm. But if LPS enters the bloodstream, it promotes inflammation in the body. (Source: Lipopolysaccharide: Basic Biochemistry, Intracellular Signaling, and Physiological Impacts in the Gut(Sang Hoon Rhee, 29 Apr 2014). Besides infection and leaky gut, LPS can enter the blood from the gut through fat-containing chylomicrons. Chylomicrons are fat transporters responsible for the absorption and transfer of dietary fat and cholesterol from the gut to the blood. This binding process is necessary to transport them to the liver for detoxification. However, not all get detoxified quickly leaving some unbound in the blood (Source: Chylomicrons promote intestinal absorption of lipopolysaccharides(Sarbani Ghoshal et al, Jan 2009). That stimulates production of inflammatory cytokines: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and CRP. It appears higher-fat meals may increase LPS and inflammation, particularly in obese people.

From leaky gut to leaky brain

The leaky gut can in turn lead to a leaky brain, that is to say permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The blood-brain barrier is how the brain protects itself from damaging, inflammatory influences. The endothelial cells of the BBB’s blood vessels fit together tightly (tight junctions) so substances such as disease-causing pathogens and toxins cannot pass out of the bloodstream into the brain.

When the BBB is compromised, neuroinflammation results. BBB crossover by the foreign molecules and cells leads to the activation of microglia. Microglia are the immune cells in the brain. Microglia regulate the pro-inflammatory activity of astrocytes, which are the most numerous cell type of the central nervous system (CNS) that perform a variety of tasks, from axon guidance and synaptic support, to the control of the blood brain barrier and blood flow. In response to the foreign invasion, the microglia activated astrocytes destroy neurons and nerve processes and initiate scar formation.

The whole process gut inflammation to neuroinflammation is schematically represented in the adjacent figure.

For further reading, see Leaky Gut, Leaky Brain?(Mark E. M. Obrenovich, 18 Oct 2018)

Some Causes of Leaky Gut

Leaky gut has long been associated with celiac disease, but there are many other causes beyond celiac disease and gluten sensitivity.

As shown in the adjacent Figure, factors that loosen the tight junctions and increase gut permeability: Western diets, saturated fatty acids, gluten, salt, alcohol and chemical additives present in processed food. Non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs and stress may also damage the gastro-intestinal tract. Stress causes deterioration of the barrier by activation of the corticotropic-releasing factor (CRF) mast cell axis. [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)] With so many contributors, is it no wonder leaky gut is so common and inflammatory health issues are rampant. Some, not necessarily all, of the causes of leaky gut are discussed below.

Gluten

Even without celiac disease, “It is known that gluten has a direct action on the mucosal barrier of the intestine [36]” [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)]

Gluten activates the protein zonulin. Zonulin is a protein that modulates the permeability of tight junctions between cells of the wall of the digestive tract. Thus zonulin loosens the tight junctions and makes the intestinal barrier more permeable. “The increased permeability of the intestinal barrier caused by gluten is particularly evident in individuals with non-celiac gluten sensitivity [36].” [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)]

“Gluten is resistant to digestion. Fragments of not completely digested gluten may be mistaken for a microbial molecule [36]” [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)] “For this reason gluten fragments cause the release of zonulin and the opening of the tight junctions. In a similar way, when in the blood stream, gluten opens another barrier equipped with tight junctions: the blood-brain barrier (BBB). As gluten fragments pass through the intestinal wall, they are recognized as a foreign molecule, similar to a viral protein. Following the opening of the barrier, other undigested dietary molecules and microbes also pass through the barrier. All the invaders trigger an immune response. Antibodies against gluten and gliadin can cross react with some brain proteins and can promote neurodegenerative diseases [39,40]. [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)]

Alcohol

“Chronic alcohol intake promotes bacterial overgrowth and gut dysbiosis [41]. It also alters the integrity of the intestinal barrier by decreasing the levels of the anti-microbial molecule REG3, thus favoring microbial access to the gut mucosa [42]…Moreover, alcohol interferes with the metabolism of fatty acids, proteins and carbohydrates, as it converts NAD+ into NADH, and is a pro-inflammatory molecule.” [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019]

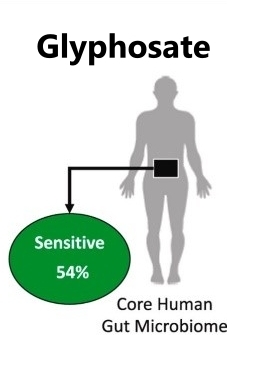

Glyphosate

Herbicides, insecticides, and pesticides introduce poisons into our bodies from the plants we eat, the animals we eat, the produce we touch, even the water we drink. While all those are problematic, glyphosate (brand name Roundup) is the most commonly used broad spectrum herbicide.

Numerous households use Roundup on their lawns. But the most common exposure comes from farmers also often spray crops with it for two reasons: (1) to control weeds, and (2) as a desiccant to aid with harvesting various crops. Glyphosate can be found in the animals and the milk of animals who are fed the grains and beans which have been sprayed with it. It has also been found to leach into water sources.

Glyphosate kills off good gut bugs potentially resulting in dysbiosis. Glyphosate also enhances gluten sensitivity, which breaks down the intestinal barrier, thus increasing leaky gut. {Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389420325462 Classification of the glyphosate target enzyme (5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase) for assessing sensitivity of organisms to the herbicide ](Lyydia Leinoa et al, 14 Nov 2020)

Additional reading on glyphosate and the gut microbiome:

- Gut microbiota and neurological effects of glyphosate(Lola Rueda-Ruzafa et al, Dec 2019)

- The Ramazzini Institute 13-week pilot study on glyphosate and Roundup administered at human-equivalent dose to Sprague Dawley rats: effects on the microbiome(Qixing Mao et al, 29 May 2018)

Chemicals in Processed Foods

“Processed food may contain diverse chemicals added to food in order to improve its stability over time and its appeal to the consumer. The additives may be preservatives, artificial flavorings, colorants, emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners and/or antibiotics. All are deleterious for the human gut microbiota [35,43–46]. For example, dietary emulsifiers decrease the gut microbiota diversity, favor inflammation and reduce the thickness of the mucus layer. Non-nutrient sweeteners (stevia, aspartame and saccharin) have a bacteriostatic effect on gut microbiota. The intake of antibiotics, which may be present in processed food, decreases microbial diversity too, but in addition may cause resistance to antibiotics. An important problem is the addition to processed foods of components from other foods, such as lactose, sugar, whey proteins, gluten, lactose and casein. These added ingredients can represent an overload of particular foods and can create intolerances." [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)]

Gut Dysbiosis

“What can damage the integrity of the intestinal barrier is first of all gut dysbiosis, often associated with the increase in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and the decrease in overall microbial diversity [19,20]. Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the most represented bacterial phyla in the intestine. Persistent dysbiosis leads to an increase in the Th17/Treg ratio and of the lipopolysaccharide LPS, and triggers intestinal inflammation. As a consequence, the tight junctions loosen and the barrier opens. What is in the lumen comes out and enters the blood stream: namely fragments of undigested food; microbes, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6; and endotoxins such as LPS, an endotoxin that is a marker of the translocation of gram-negative bacteria [47,48]. As a result, systemic endotoxemia, chronic systemic inflammation and chronic inflammatory diseases develop. Since intestinal dysbiosis depends primarily on our dietary habits and our life-style, we are the ones who cause intestinal inflammation, the opening of the intestinal barrier, and the metabolic and chronic diseases of our time. Among them it is possible to associate to gut dysbiosis the development of neurodegenerative diseases, which have an inflammatory basis.” [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)] Beyond causing leaky gut, gut dysbiosis is further discussed below in the Gut Microbiome section.

Signs and Symptoms of Leaky Gut

Problems and imbalances in our gut can cause far more than just a stomach ache, they can be the root cause of many chronic health problems. Since the causes and symptoms are so diverse, pinpointing an issue as leaky gut is admittedly challenging.

Symptoms of leaky gut include:

- Bloating and fluid retention

- Diarrhea and constipation

- Fatigue and chronic fatigue

- Headaches, brain fog, memory loss, difficulty concentrating

- Cravings for sugar or carbs

- Poor immune system, Autoimmune diseases

- Mood imbalances such as depression and anxiety

- Skin issues – rashes, acne, eczema, rosacea

- Arthritis, Joint pain and fibromyalgia

- Thyroid conditions

- Arthritis or joint pain

- Cholesterol markers

Regarding that last bullet, cholesterol markers

- The significant association between increased gut permeability and elevated serum HDL-cholesterol is consistent with the role of HDL as an acute phase reactant, and in this situation, potentially dysfunctional lipoprotein. This finding may have negative implications for the putative role of HDL as a cardio-protective lipoprotein. [Source: Elevated high density lipoprotein cholesterol and low grade systemic inflammation is associated with increased gut permeability in normoglycemic men(M D Robertson et al, Dec 2018)]

Additionally,

- The connection between gastrointestinal inflammation or microbiome imbalances and cholesterol levels in the blood is a bit more complex, but it has been established that when gram negative bacteria from the gut produce an abundance of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and this LPS slips through the gut barrier, being picked up in the blood stream, LDL cholesterol levels may rise in response to this increased toxic load coming from the gut [5, 6].

- When this happens, seeing LDL cholesterol levels rise is actually a good sign that the body’s built-in defenses are responding to this inflammatory threat coming from the gut.

- It is still a sign that an inflammatory imbalance of bacteria exists in the gut, however, and you may need to do further testing to assess how best to intervene when this has happened.

[Source: The Link Between Your Gut Health and Cholesterol(by VibrantWellness)]

Addressing a Leaky Gut

Some measures to treat a leaky gut:

Eliminate damaging foods Gluten (even if tested negative for celiac disease), non-organic foods (pesticide treated, aka GMO), processed foods, alcohol, and whatever other foods you are individually sensitive to. Cut them out for at least three months and avoid in excess thereafter.

Reduce stress Stress hormones break down the tight junctions of the digestive tract. Take time to relax, stretch, do breathing exercises, meditate, practice mindfulness.

Fast/Dietary restriction Food availability 24/7 is a recent phenomenon. For much of human history there were times of food paucity. As the ancestral gene, ApoE4s are especially well suited to food deprivation. The microbiota of the large intestine is especially dependent on fasting.

“Fasting for several days, fasting mimicking diet (FMD) [59], intermittent fasting, short term fasting, caloric restriction and time restricted feeding [60] are different fasting or food restriction plans that have been recently proposed to improve health. All improve the integrity of the intestinal barrier, induce a higher microbial diversity, and counteract intestinal inflammation [61–63]. [Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity (Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019)]

Generate butyrate The short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate is a metabolite produced by intestinal bacteria through the fermentation of nondigestible polysaccharides (dietary fiber).

Butyrate holds numerous health benefits, one of which is keeping the gut lining healthy and functioning properly. "At the intestinal level, butyrate plays a regulatory role on the transepithelial fluid transport, ameliorates mucosal inflammation and oxidative status, reinforces the epithelial defense barrier, and modulates visceral sensitivity and intestinal motility." [Source: Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases(Roberto Berni Canani et al, 28 Mar 2011)] There is more discussion on butyrate beyond leaky gut below under the Gut Microbiome section.

Add collagen Such foods as bone broth, gelatin, and collagen powders can help mend a leaky gut. Also the body can produce its own collagen through such foods as eggs, citrus fruits, broccoli, sunflower seeds, and mushrooms. Collagen contains the amino acids glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline that are needed to repair and rebuild your gut lining. Supplemental collagen peptides can help to strengthen the gut barrier, making it less permeable. [Source: Collagen peptides ameliorate intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in immunostimulatory Caco-2 cell monolayers via enhancing tight junctions(Qianru Chen et al, 22 Mar 2017)] Adding bone broth during a fast could doubly help repairing a leaky gut, plus bone broth can help satisfy feelings of hunger.

Exercise Exercise benefits more than just muscles, it improves circulation, transport of oxygen, and helps promote diversity of gut microbes. [Source: Gut microbiota diversity is associated with cardiorespiratory fitness in post‐primary treatment breast cancer survivors(Stephen J. Carter et al, 14 Feb 2019)]

Sleep Sleep is regenerative, it is a time of fasting, (discussed above as improving the integrity of the intestinal barrier) detoxification and repair. Ideally one’s bedtime should be 3-4 hours after the last meal, with no late night snacks. This gives the body a chance to direct its energy while sleeping to detoxification and autophagy (cellular housecleaning) not digestion. When the body is faced with having to choose between digestion and cellular cleansing, it will prioritize digestion thus neglecting the important cleansing processes.

Vitamin A+D

- It has been recently shown that vitamin A improves the integrity of the intestinal barrier, even in the presence of intestinal inflammation and higher LPS level. It seems to counteract the action of LPS and to enhance the expression of tight junction proteins [78].

- However, vitamin A is not sufficient. As reported in our previous review [25], vitamin A and vitamin D have synergistic anti-inflammatory effects and should be administered together. This is not surprising as they are both liposoluble and often present together in the same food. Their nuclear receptors cooperate if both vitamins are bound to them. Shared functions of vitamin A and vitamin D include the enhancement of tight junction proteins, the suppression of IFN-γ and IL-17, and the induction of regulatory T cells (Treg) [79]. Finally, vitamins A and D are effective against chronic inflammation and favor the stability of the intestinal barrier. Their action on microbiota is not direct as their nuclear receptors are expressed only by the host, not by the microbiota. Deficiency in vitamin D leads to disruption of the intestinal barrier, gut dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation [80].”

[Source: Undigested Food and Gut Microbiota May Cooperate in the Pathogenesis of Neuroinflammatory Diseases: A Matter of Barriers and a Proposal on the Origin of Organ Specificity(Paolo Riccio and Rocco Rossano, 9 Nov 2019]

GUT MICROBIOME

The human body is host to a number of microbiomes: oral (ear, nose and throat), skin, lung, urinary tract, vagina, and the largest by far with 100 trillion microorganisms, the gut (the gastrointestinal tract, with the majority, approximately 70% , housed in the colon). Our bodies host far more microorganisms than cells. The gut microbiota, sometimes called gut flora, consist of such microorganisms as bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, and archaea.

The human body is host to a number of microbiomes: oral (ear, nose and throat), skin, lung, urinary tract, vagina, and the largest by far with 100 trillion microorganisms, the gut (the gastrointestinal tract, with the majority, approximately 70% , housed in the colon). Our bodies host far more microorganisms than cells. The gut microbiota, sometimes called gut flora, consist of such microorganisms as bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, and archaea.

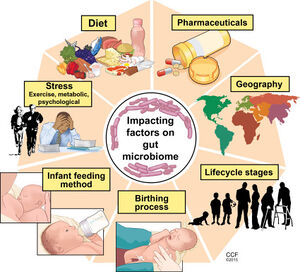

The “seeds” of our gut microbiome comes from the mother’s own intestinal microbiota. We get our first dose of microbes at birth while traveling through the birth canal. The rest come through bacteria from breastfeeding, At least that’s how humans did it for most of our history, until recent times with cesarian section births and canned baby formula. Evidence suggests that births by cesarean section impact a baby’s immune system. If facing a cesarean section birth, insist on a vaginal swab, also known as vaginal seeding, to transfer the vaginal flora to the newborn infant.

For the vast majority of human history all humans were ApoEε4/4s. Also for most of human history, man ate what he could find. Man roamed from place to place in search of food influenced by the seasons, migration patterns, and growth cycles of plants. It was only in the last 100,000 years (recent in human evolutionary terms) that man jumped to the top of the food chain, before that time the human diet consisted of hunted small creatures, insects, and whatever plant based food that they could forage.

From the book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari, PhD, "The foragers’ secret of success, which protected them from starvation and malnutrition, was their varied diet. … Furthermore, by not being dependent on any single kind of food, they were less liable to suffer when one particular food source failed. … Ancient foragers also suffered less from infectious diseases." (pages 58-59, Kindle location 843- 853).

Through human history a mutualistic (beneficial to both parties) albeit complicated relationship evolved between man and his microbes. But our precious gut microbiome, the basis for healthy function of our nutritional, immune, hormonal, and neurological systems has been devastated with our modern sedentary, stressful, over-sanitized lives eating a limited, unvaried diet overrun with sugar and simple carbohydrates, devoid of fiber, and exposed to antibiotics, herbicides, pesticides, plastic wrapping, preservatives, additives and other unnatural exposures.

While mostly established by age 3, the microbiome is not static, there are many factors which impact its diversity and composition, such as age, diet, stress, and drugs.

Gut Eubiosis

When the intestinal microbial ecosystem is in balance, this is called eubiosis. “A healthy intestinal microbial ecosystem is balanced but flexible enough to tolerate the intrusion of potential pathogens … A healthy intestinal flora is essential to promote the health of the host, but the excessive growth of the bacterial population leads to a variety of harmful conditions.” (Source: Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota(Valerio Iebba et al, 2016).

Gut Dybiosis

Dysbiosis is when the “good” gut bugs no longer control the “bad" gut bugs and the bad bugs take over. Dysbiosis is associated with a number of negative health consequences.

Causes of gut dybiosis.

- When there is an interruption in the balance of microbiota, it can lead to dysbiosis. There are many possible causes of this condition. A dietary change wherein there is an increased intake of sugar, protein, and food additives may lead to dysbiosis. The other causes include frequent antibiotic use, excessive alcohol consumption, frequent antacid use, accidental ingestion of pesticides or exposure to chemicals, chronic physical or psychological stress, previous parasitic or bacterial infection of the gastrointestinal tract, and a diet that is low in fiber.

- Other causes include consuming new medications that can affect the gut flora, poor dental hygiene, anxiety, and unprotected sex that can expose the person to bacteria. Some studies have linked being formula fed and born via C-section, as some factors can change the type of strains of beneficial bacteria present in newborns. These factors can increase the risk of developing gut dysbiosis in later life. (Source: Preventing Dysbiosis(Angela Betsaida B. Laguipo, BSN, 8 Oct 2018)

Reestablishing Eubiosis Many therapeutic strategies have been developed to reestablish intestinal eubosis and new strategies are constantly being investigated, but the best known and most adopted therapeutic strategies are probiotics and prebiotics.

Probiotics are live microorganisms (good gut bugs) that are found in fermented products like yogurt, kimchi and sauerkraut. Not all fermented foods qualify as probiotic, there must be sufficient beneficial living bacteria that survive such that they’re found in the final food or beverage. Probiotics are also found in dietary supplements. The gut microbiome is dominated by two main groups of bacteria: Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. The two bacteria commonly labeled as probiotics are Lactobacillus, which is in the Firmicutes group, and Bifidobacterium, a type of Actinobacteria. An important consideration when choosing to consume probiotics is to select a probiotic that will actually be helpful which means the microorganisms need to be able to survive stomach acid. For example, using a product that contains BC30. BC30 is a patented strain of probiotic bacteria designed for resilience. Studies have shown it can survive 100 times better than those found in yogurt and other probiotics.

Prebiotics are food for the good gut bugs. Prebiotics are found in high-fiber foods. The fiber isn’t broken down by the digestive enzymes so it passes to the large intestine undigested where it is fermented by the gut bacteria. Inulin and oligosaccharides are also classified as prebiotics. The Western Diet, followed by so many, is low on fiber consumption. The average American eats about 16 grams of fiber per day, while the recommendation is 25 to 38 grams of fiber a day. (Source: Nutrition 101: Prebiotics, Probiotics and the Gut Microbiome(Allison Webster, PhD, RD, 17 Apr 2019)

When the gut metabolizes prebiotics, short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, acetate, and propionate are produced. As shown in the adjacent figure Butyrate has many health benefits, including: intestinal barrier fortification, ameliorating inflammation and oxidation, cell growth and differentiation, intestinal motility and visceral perception, immune regulation, and ion absorption.

Of particular interest to ApoE4s, researchers of this paper Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Lipopolysaccharide as Mediators Between Gut Dysbiosis and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease( Marizzoni, Moira et al, 10 Nov 2020) found that high levels of butyrate was associated with less amyloid pathology in the brain.

Another subject of interest when discussing the gut microbiome is trimethylamine N-oxide abbreviated TMAO. TMAO is a metabolite produced when gut bacteria digest choline, lecithin and carnitine, nutrients that are abundant in animal products. The saturated fat in animal products used to be singled out as raising the risk of heart disease, but these recent findings on the effects of have clouded the situation. Studies have found high blood levels of TMAO to be associated with a higher risk for both cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality (early death from any cause).

Gut Microbiota Resilience: Definition, Link to Health and Strategies for Intervention(Shaillay Kumar Dogra et al, 15 Sep 2020)

Microbiota modulate sympathetic neurons via a gut–brain circuit(Paul A. Muller et al, 8 Jul 2020)

Gut Microbiota during Dietary Restrictions: New Insights in Non-Communicable Diseases(Emanuele Rinninella et al,28 Jul 2020)

Rapid improvement in Alzheimer’s disease symptoms following fecal microbiota transplantation: a case report(Sabine Hazan, 30 Jun 2020)

The Role of the Gastrointestinal Mucus System in Intestinal Homeostasis: Implications for Neurological Disorders(Madushani Herath et al, 28 May 2020)

Crosstalk Between the Gut Microbiome and Bioactive Lipids: Therapeutic Targets in Cognitive Frailty(Liliana C. Baptista et al, 11 Mar 2020)

The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication(Ygor Parladore Silva et al, 31 Jan 2020)

Dynamics of Human Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Response to Dietary Interventions with Three Fermentable Fibers(Nielson T. Baxter et al, 1 Mar 2019)

Gut microbiota in neurodegenerative disorders(Suparna Roy Sarkar and Sugato Banerjee, Mar 2019)

Do gut bacteria make a second home in our brains?(Kelly Servick 9 Nov 2018)

Butyrate and Dietary Soluble Fiber Improve Neuroinflammation Associated With Aging in Mice(Stephanie M. Matt et al, 14 Aug 2018)

Unhealthy gut, unhealthy brain: The role of the intestinal microbiota in neurodegenerative diseases(Lindsay Joy Spielman et al, 14 Aug 2018)

The Human Microbiota in Health and Disease(Baohong Wang et al, Feb 2017)

Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health?(Megan W.Bourassa et al, Jun 2016)

Minireview: Gut Microbiota: The Neglected Endocrine Organ(Gerard Clarke et al, 3 Jun 2014)

Impacts of Plant-Based Foods in Ancestral Hominin Diets on the Metabolism and Function of Gut Microbiota In Vitro(Gary S. Frost et al, May 2014)

Resistant Starch: Promise for Improving Human Health(Diane F. Birt et al Nov 2013)

VAGUS NERVE

The Vagus Nerve is what physically connects the gut to the brain. The vagus nerve is one of the longest nerves in the body extending from the brain to the gut. Signals are sent through the nerve in both directions.

For information on the Vagus Nerve, including how to tap into the Vagus Nerve for healing purposes, see Vagus Nerve